"mandarin"

a member of any elite group; leading intellectual, political figure, etc., sometimes one who is pompous, arbitrary, etc.

With this definition, I've naturally always seen the word to have a fairly elitist and derogatory connotation.

The English origins of the word "mandarin" are in Chinese imperial and colonial history pertaining to the various classes, officials and ranks of social nobility with whom foreigners would largely engage and interact. "Mandarin" is a word only used outside China to identify a particular flavour of language previously associated with this class of society.

As is common in many countries with non-European social origins across Asia and Africa, China has always been a multilingual land / nation / kingdom / country with distinct languages — most famously, Cantonese, Tibetan, Uyghur — and hundreds of highly-regional dialects of "Chinese" (Mandarin, Wu, Hakka, Hui, Yue to name just the few that I've been exposed to).

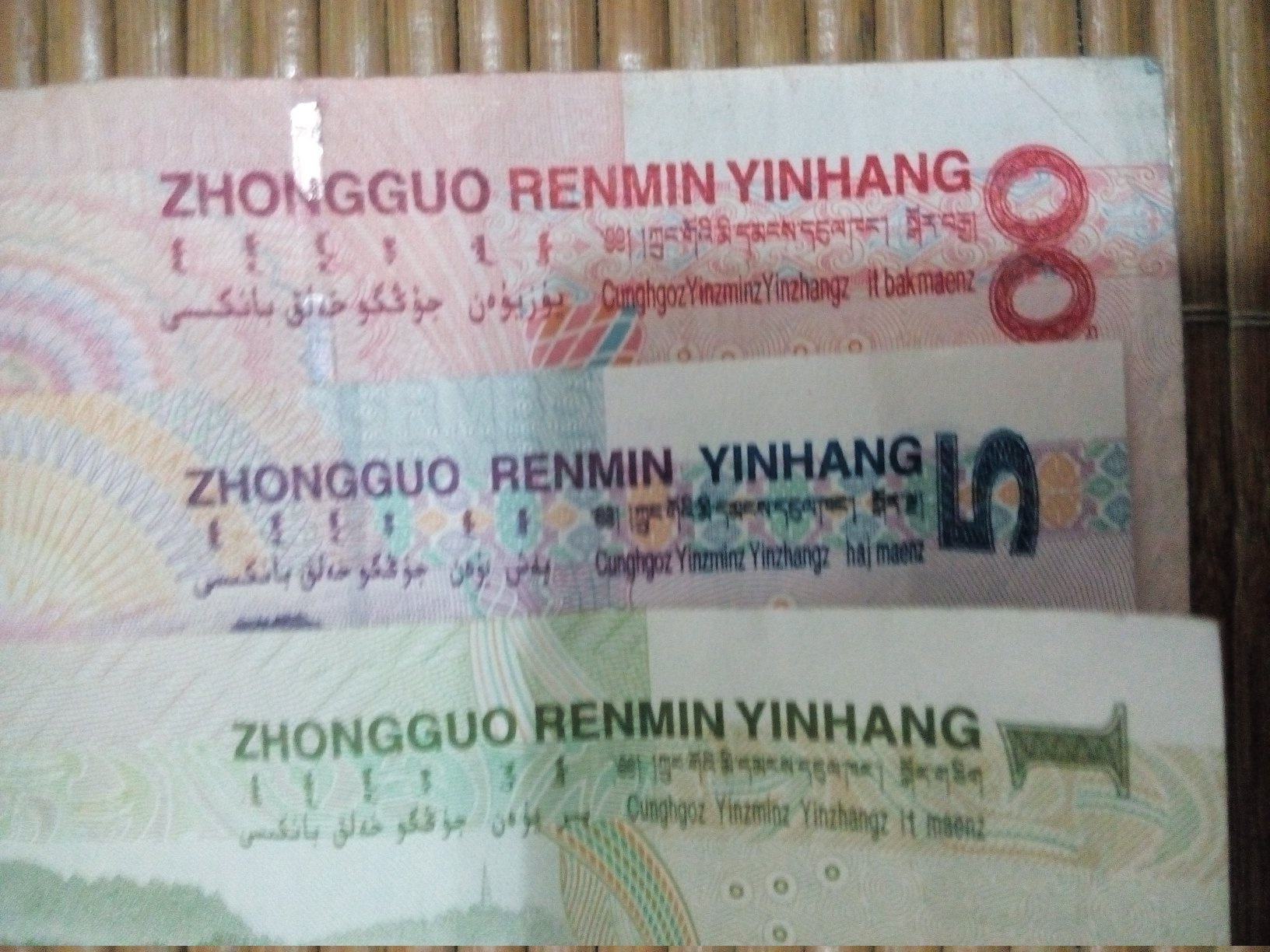

China's RMB currency with Mongolian, Tibetan, Uyghur and Zhuang languages, in addition to Mandarin Pinyin

China's RMB currency with Mongolian, Tibetan, Uyghur and Zhuang languages, in addition to Mandarin Pinyin

With their own richness of local dialects, some Europeans from Spain, Germany and Italy tend to have an easier comprehension of this ideal.

Yet we never say that we're learning "Castillian" or "Murcian" or "Valencian" or any other dialect. We say we're learning "Spanish".

Classes are rarely offered in "Frisian", "Thüringisch", or "Bavarian", but merely as "German" (most often, Hochdeutsch).

An Italian language immersion program seldom goes past the specific, "unified Italian" flavour of dialect and accent.

Much as was the case in most European countries during their formation and modern amalgamation, modern China went through a period of language transition, simplification and increase in public access to knowledge. The group of languages considered during the process included the 'Beijing' dialect, which now forms a large part of the basis of "Standard Chinese" or "Simplified Chinese". In fact, the Chinese word for "Standard Chinese" is "putonghua" 普通话 (pinyin: Pǔtōnghuà ), which translates to "common tongue", "common language", "language of the people" [1]. This meaning stands diametrically opposed to the connotation and sentiment of "mandarin".

Translation engines (Google, DeepL) with data sets seeded from academic language roots have already made this adjustment. The phrase "they speak Chinese" translates to "falam chinês" and "hablan chino" in Portuguese and Spanish respectively.

It feels like colloquial use of the word "Mandarin" in English and other European-origin languages (e.g. Portuguese) should end.

There's still the whole naming of "mandarin" oranges -- with name derived from German Apfelsine (Apfel + Sina), "chinese apple" [2] — but that's fruit for a whole other article. 🍊